A personal view about the music of John Williams and its role in my upbringing

This is a piece I wrote for the website thelegacyofjohnwilliams.com, curated by my brother Maurizio, who is doing a remarkable job in "building a platform to celebrate and promote the cultural and aesthetic importance that the music of John Williams had (and it’s still having) on many people around the world".

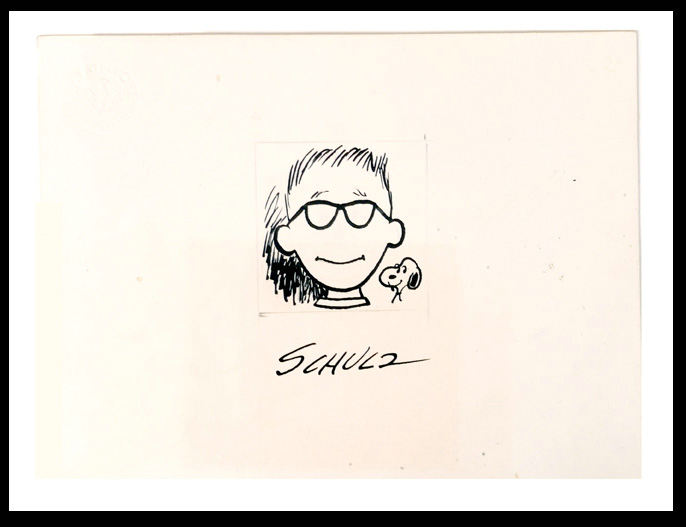

I'm honored to having contributed the illustration for the header of the website, you can see here below.

Thanks to Maurizio for allowing me to me share my thoughts on his website.

I'm honored to having contributed the illustration for the header of the website, you can see here below.

Thanks to Maurizio for allowing me to me share my thoughts on his website.

As I am typing this, the sound of my son practicing scales on the piano resonates through the house.

I think back to my short-lived affair with the instrument.

I was about seven years old and I wanted to learn how to play piano from one of my older brothers, but he had just left to study in Rome. I was put under the tutelage of another teacher; whose lessons were tedious and devoid of the kind of fun I used to have around my brother. I quit after six months, a decision I still regret. But I wasn’t left without musical mentors.

Thinking of my older brother, a recent conversation we had springs to my mind about the different music teaching methods. He was telling me a funny anecdote involving an acquaintance of his, who wanted to educate his son outside of the western tonal system, to spare him from the conditioning imposed by our musical tradition, which puts certain intervallic relationships (like the tonic-dominant) above other possible modes. Ironically, this person’s efforts were made vain by the many nursery rhymes that the kid learned at school—nothing stick to our brains like simple, diatonic major melodies.

What’s the point of this story? Well not so much to discuss the pros and cons of equal temperament, but rather to point out how glad I am to be able to participate in the conversation. Because despite having given up on piano (or any other instrument for that matter) I’m not musically illiterate.

And for that I must thank John Williams.

Make no mistakes: I admit that the reason I gravitated towards Mr. Williams’ music were the movies he scored. Like many kids in the 1980s, I was utterly captivated by movies like Star Wars, Superman or E.T. They were perfectly executed pieces of fiction easy to fall in love with. Listening to those scores was a pathway to that sense of wonderment and excitement those movies provided.

But on repeated listening, the richness of these scores started to intrigue me. The dramatic drive of the pieces made the narrative clear, so I could tell at which point of the story I was listening to. The melodic writing made every moment memorable and singable. The rich instrumentation and length of the cues sustained my interest. So much that, as a teen ager, it took a long time to adjust my ears to the pop-music I was “supposed” to listen in the 1990s, to keep at pace with my schoolmates, who were into grunge, indie rock or Britpop.

But no matter how important John Williams music was to ignite my interest in music, you need teachers in flesh and blood to make the seed blossom.

Luckily, I had at least one: Umberto Bombardelli, a composer himself, who taught music at my middle school. He could have come right out of movies like Mr. Holland’s Opus or Goodbye, Mr. Chips—he even looked like Peter O’ Toole in that 1969 movie (with music adapted and conducted by John Williams, by the way).

At the time, music was a mandatory subject in Italy for students in middle school between the age of 11 and 14, but it was easily disregarded as an extra or a commodity, certainly not the subject that would make or break your graduation. However, Mr. Bombardelli taught passionately, with patience and humor, becoming soon known by his pupils as “the good teacher”.

He did a lot more than just make us play the recorder or put on Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. He made us listen to various type of music (from Palestrina to Demetrio Stratos and Luciano Berio), teaching us about the different musical periods and styles. He even showed us movies and made us pay attention to the music (The Blues Brothers, Walt Disney’s Fantasia and also the Williams-scored The Cowboys). To this day, I owe him for laying the foundations of any musical knowledge I may have.

As I grew up, I gravitated towards Romantic or Post-Romantic composers, whose works shared a lot of common traits with the type of film music me and my brother Maurizio learned to love, from John Williams to Jerry Goldsmith, Alan Silvestri and Danny Elfman. The two pieces that encouraged me to explore the very rich catalog of classical music were the symphonic suite from George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (the great London Symphony Orchestra recording conducted by the late great André Previn) and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade as recorded by Fritz Reiner with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for RCA (this one kindly recommended by my brother Alessandro).

We used to have a public radio station that aired classical music nonstop 24/7 (the so-called filodiffusione, which is now part of the bouquet of radio channels managed by the Italian national broadcasting service, a.k.a. RAI) and I was listening to it at every possible moment—I once spent two hours pretending to pay attention during a class in high school while I was listening to Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No.3 through an earpiece hidden in my hand (true story).

From there it has been a fantastic voyage through multi-colored soundscapes. A journey I still enjoy every day. Today I do not have to rely on a fortuitous encounter with a dedicated teacher or on state-owned radio stations, the internet made it possible to discover and share gems very easily.

But it all started thanks to John Williams. And his music still works magnificently as gateway to musical appreciation.

In the meantime, the sound of scales has been swapped for more familiar tunes, as my son now plays the “Flying Theme” from E.T. and then “The Imperial March”, and then the Theme from Schindler’s List. I hear him stumble or hitting a wrong note here and there, but the pleasure he has in playing the music is palpable. Since I showed him Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie, he became a big fan, so much so that he asked for the sheet music as present for Christmas. Even my wife, who does not care much about film music (but who has, unlike me, stuck to her piano lessons and CAN actually play the thing) is starting to warm up to Williams’s infectious tunes.

My mind wanders again: I now think of a painting one of my art teachers once did. It was called Music, a gift from heaven. It depicts a mandolin and a dove, against puffy clouds.

It was well drawn, but incredibly cheesy. But I do share the feeling.

And whether this gift comes from gods, from heaven or from nature, I will forever be grateful to Mr. Williams for delivering it to me.

---

The video here below, put together by composer Austin Wintory reflects many of the same feelings.

I think back to my short-lived affair with the instrument.

I was about seven years old and I wanted to learn how to play piano from one of my older brothers, but he had just left to study in Rome. I was put under the tutelage of another teacher; whose lessons were tedious and devoid of the kind of fun I used to have around my brother. I quit after six months, a decision I still regret. But I wasn’t left without musical mentors.

Thinking of my older brother, a recent conversation we had springs to my mind about the different music teaching methods. He was telling me a funny anecdote involving an acquaintance of his, who wanted to educate his son outside of the western tonal system, to spare him from the conditioning imposed by our musical tradition, which puts certain intervallic relationships (like the tonic-dominant) above other possible modes. Ironically, this person’s efforts were made vain by the many nursery rhymes that the kid learned at school—nothing stick to our brains like simple, diatonic major melodies.

What’s the point of this story? Well not so much to discuss the pros and cons of equal temperament, but rather to point out how glad I am to be able to participate in the conversation. Because despite having given up on piano (or any other instrument for that matter) I’m not musically illiterate.

And for that I must thank John Williams.

Make no mistakes: I admit that the reason I gravitated towards Mr. Williams’ music were the movies he scored. Like many kids in the 1980s, I was utterly captivated by movies like Star Wars, Superman or E.T. They were perfectly executed pieces of fiction easy to fall in love with. Listening to those scores was a pathway to that sense of wonderment and excitement those movies provided.

But on repeated listening, the richness of these scores started to intrigue me. The dramatic drive of the pieces made the narrative clear, so I could tell at which point of the story I was listening to. The melodic writing made every moment memorable and singable. The rich instrumentation and length of the cues sustained my interest. So much that, as a teen ager, it took a long time to adjust my ears to the pop-music I was “supposed” to listen in the 1990s, to keep at pace with my schoolmates, who were into grunge, indie rock or Britpop.

But no matter how important John Williams music was to ignite my interest in music, you need teachers in flesh and blood to make the seed blossom.

Luckily, I had at least one: Umberto Bombardelli, a composer himself, who taught music at my middle school. He could have come right out of movies like Mr. Holland’s Opus or Goodbye, Mr. Chips—he even looked like Peter O’ Toole in that 1969 movie (with music adapted and conducted by John Williams, by the way).

At the time, music was a mandatory subject in Italy for students in middle school between the age of 11 and 14, but it was easily disregarded as an extra or a commodity, certainly not the subject that would make or break your graduation. However, Mr. Bombardelli taught passionately, with patience and humor, becoming soon known by his pupils as “the good teacher”.

He did a lot more than just make us play the recorder or put on Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. He made us listen to various type of music (from Palestrina to Demetrio Stratos and Luciano Berio), teaching us about the different musical periods and styles. He even showed us movies and made us pay attention to the music (The Blues Brothers, Walt Disney’s Fantasia and also the Williams-scored The Cowboys). To this day, I owe him for laying the foundations of any musical knowledge I may have.

As I grew up, I gravitated towards Romantic or Post-Romantic composers, whose works shared a lot of common traits with the type of film music me and my brother Maurizio learned to love, from John Williams to Jerry Goldsmith, Alan Silvestri and Danny Elfman. The two pieces that encouraged me to explore the very rich catalog of classical music were the symphonic suite from George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (the great London Symphony Orchestra recording conducted by the late great André Previn) and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade as recorded by Fritz Reiner with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for RCA (this one kindly recommended by my brother Alessandro).

We used to have a public radio station that aired classical music nonstop 24/7 (the so-called filodiffusione, which is now part of the bouquet of radio channels managed by the Italian national broadcasting service, a.k.a. RAI) and I was listening to it at every possible moment—I once spent two hours pretending to pay attention during a class in high school while I was listening to Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No.3 through an earpiece hidden in my hand (true story).

From there it has been a fantastic voyage through multi-colored soundscapes. A journey I still enjoy every day. Today I do not have to rely on a fortuitous encounter with a dedicated teacher or on state-owned radio stations, the internet made it possible to discover and share gems very easily.

But it all started thanks to John Williams. And his music still works magnificently as gateway to musical appreciation.

In the meantime, the sound of scales has been swapped for more familiar tunes, as my son now plays the “Flying Theme” from E.T. and then “The Imperial March”, and then the Theme from Schindler’s List. I hear him stumble or hitting a wrong note here and there, but the pleasure he has in playing the music is palpable. Since I showed him Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie, he became a big fan, so much so that he asked for the sheet music as present for Christmas. Even my wife, who does not care much about film music (but who has, unlike me, stuck to her piano lessons and CAN actually play the thing) is starting to warm up to Williams’s infectious tunes.

My mind wanders again: I now think of a painting one of my art teachers once did. It was called Music, a gift from heaven. It depicts a mandolin and a dove, against puffy clouds.

It was well drawn, but incredibly cheesy. But I do share the feeling.

And whether this gift comes from gods, from heaven or from nature, I will forever be grateful to Mr. Williams for delivering it to me.

---

The video here below, put together by composer Austin Wintory reflects many of the same feelings.